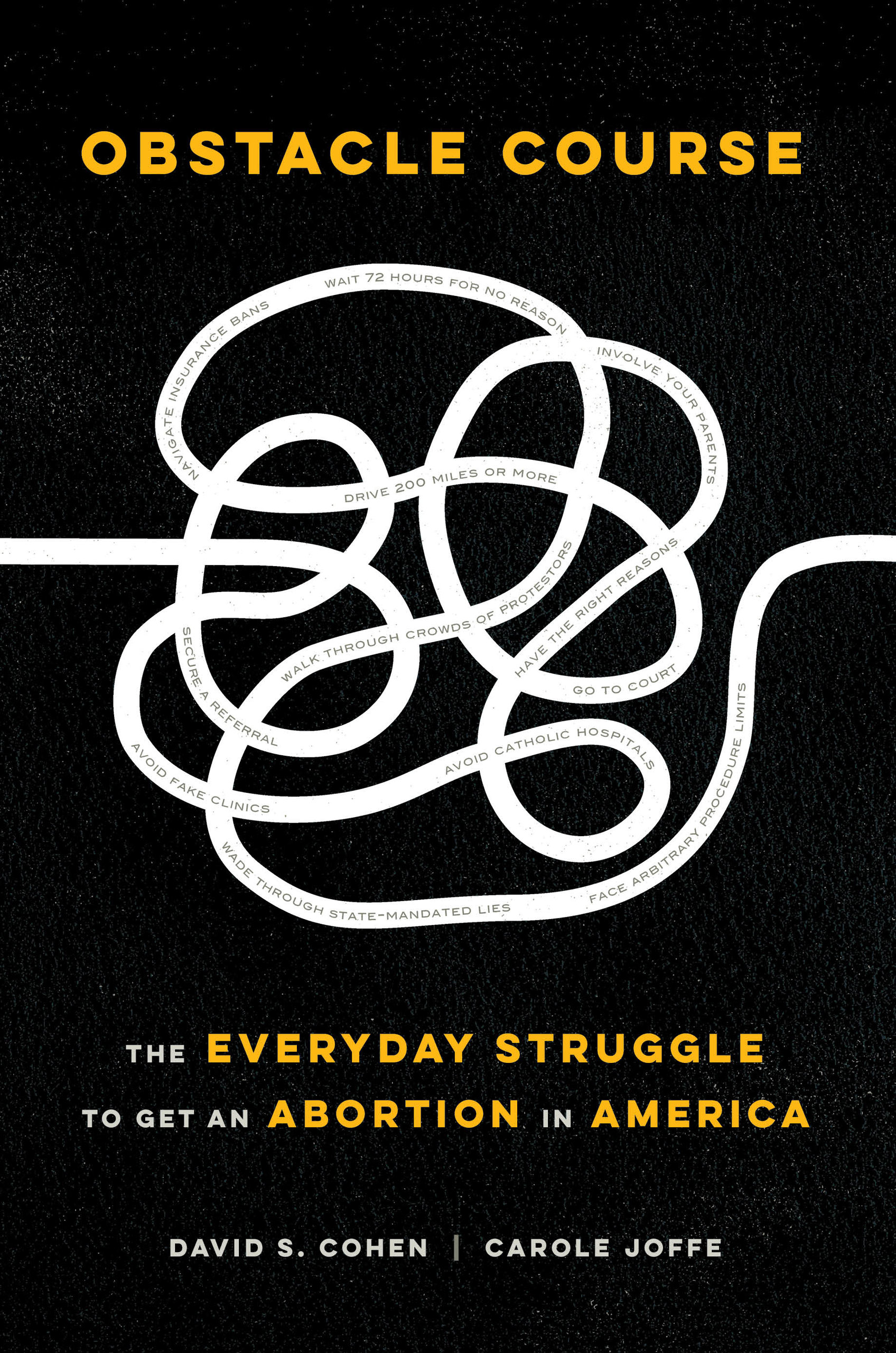

Obstacle Course is a new book that explores the obstacles most Americans must navigate to access safe legal abortion care in the wake of a blitz of state-level bills designed to reserve abortion access for the relatively wealthy and geographically lucky.

It’s one thing to read daily news coverage of the seemingly never-ending onslaught of abortion restrictions coming down in states across the country. We know that each one designed to add another hurdle, cost a would-be patient a little more money, and drive a bit further. This is what so many Americans must do in order to access legal, constitutional, evidence-based reproductive healthcare.

Now, amid coronavirus, there are even more obstacles, including states lawmakers exploiting the pandemic as an opportunity to coerce pregnant people into birth against their will and anti-abortion street protesters defying stay-at-home orders to gather and harass patients, among other tactics.

While we are used to reading such news, it’s very powerful to read about how these obstacles informs and affects the experience of people trying to access care.

Abortion access in the United States was severely stratified before Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973. Now, a decade into the blitz of abortion restrictions that began in earnest in 2010, it’s clear the anti-abortion effort has re-created a stratified reproductive healthcare system where ordinary Americans must navigate an obstacle course to obtain safe, legal abortion care.

Meanwhile, we are awaiting a ruling in June Medical Services v. Russo, the first U.S. Supreme Court abortion rights case since Trump installed two judges.

WLP’s Tara Murtha talked with constitutional law professor and WLP board member David S. Cohen about Obstacle Course, the urgently needed and timely new book co-authored with Carole Joffe, Ph.D. Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Sciences Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH).

WLP: Let’s start by discussing the genesis of Obstacle Course and the reporting process.

After the Whole Woman’s Health decision I was thinking about ways to try to show how all the various abortion restrictions impact access to safe legal abortion, especially since the Court said in that case that we have to pay attention to evidence-based reality.

So I thought of creating a book that could pack in all the restrictions, and all the evidence about how they impact care, while also talking with abortion providers about how they still deliver high-quality care in light of these restrictions.

My co-author, Carole Joffe, agreed this would be a good idea so we decided to work on it together. We interviewed abortion providers and allies from every state in the country as well as the two major territories, DC and Puerto Rico, so we could paint a picture about how all these restrictions operate while also showing how people provide care in states without restrictions.

We used patient stories that were publicly available. We wanted to talk to providers who care for patients to see how they are still able to do their job and do their job well while being subject to these unnecessary restrictions.

We also wanted to talk with “practical support” people, people who fund abortions, people who drive patients to procedures, who house them overnight, escorts, people who make it possible for patients to access care without providing the care themselves.

WLP: You’ve been tracking reproductive health policy and law for a long time. What have you seen change in terms of what you call “practical support?”

There’s greater and greater recognition that logistical support is needed, and more and more groups are popping up—anything from a standard formal organization with paid staff to volunteer groups trying to meet this need. The Internet makes it easier to connect with clinics and patients and make this happen.

The big difference between now and 20 years ago is that we’ve had so many clinic closures in the last decade, the high number of clinic closures means it’s harder to find or get to clinics. Sometimes a patient is traveling hundreds of miles to a clinic where they can’t sleep in their own home and don’t have a car or reliable transportation. They need that help.

So some of the need is new, and some part of the need is not new at all.

WLP: The “obstacle course” begins upon the discovery of pregnancy. What are the other steps?

We organized the book in chronological order, from the moment you find out you’re pregnant, to getting the procedure, and all the ways legislation and other aspects of society interfere with someone’s process of moving from finding out they’re pregnant to getting an abortion.

We start with interference with making the decision. We talk about how difficult it can be to find and get to a clinic, the challenge of physically getting into the clinic, difficulty paying for the procedure, how laws interfere with the counseling process, mandatory delays or waiting periods, and then restrictions on the actual procedure itself.

So we walk through all those different steps and show how burdensome the process has been made by the government rather than for medical reasons.

WLP: Did you find attrition of determination to secure an abortion in patient stories when they had to navigate such a difficult obstacle course?

In some ways, the book is very depressing because it shows all these barriers. But in other ways, the book shows patients are resilient and will do everything they can to fight through these barriers, and they will do so at a high cost to their financial situation and medical situation. When people want and need an abortion they will, for the most part, try hard to get one. That doesn’t mean everyone can make it through this obstacle course, but with the help of abortion providers and allies that we interviewed, a very large number can get through the course.

So in some ways, the book is a testament to their determination.

WLP: Let’s talk about race. Is a Black women’s obstacle course typically different than a white woman’s? How does race inform the obstacle course?

Most of the things we talk about in the book disproportionately impact poor women and, given the connection between race and poverty in this country, that means a disproportionate impact on women of color, particularly Black women. Add on to that the fact that protesters will separately target Black women and other women of color, yelling racist epithets or racialized comments at them. The combination of race and class just makes this obstacle course even harder for women of color.

WLP: Do we know what happens to people who wanted and needed abortion care but were turned away due to lack of funds, or transportation, or a combination of obstacles?

There’s an incredible study out of Advancing New Studies in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) called the Turnaway Study that looks at what happens to people who are turned away from getting an abortion for various reasons. The study has shown that those people are worse off compared to those who get an abortion across so many different measures: economically, psychologically, in terms of their risk of domestic violence, physical health, children’s health, aspirations for the future, and so forth. There are almost 50 different papers that look at these measures, and they all find all the ways the inability to find abortion care affects people’s lives.

WLP: I’m glad you brought up the welfare of children because that is something that many people don’t consider.

They forget that 60% of people who have abortions are mothers, which means that any burden that is imposed on them is also imposed on their children.

WLP: The first story in the book tells us the plight of Talia, a teenager with an unplanned pregnancy who winds up at a crisis pregnancy center while searching for an abortion. It’s horrifying. She’s talking to anti-abortion activists in Halloween costume lab coats pretending to be doctors, and when they can’t coerce her decision they ultimately pretend to schedule an abortion but tell her she has to wait a few weeks. I’m aware this coercion technique is known as “running out the clock.” How common was that experience among the people you interviewed?

One of the few good things we know about CPCs is that the evidence shows is that most of their clients don’t walk through the door wanting an abortion. That being said, regarding the ones who do, we heard many stories about patients being told incorrect information about the date of their pregnancy, in both directions.

If you tell someone they are 18 weeks pregnant when the local abortion provider only goes to 16 weeks, then they think they can’t have an abortion. But if you tell them they’re 12 weeks and they have all sorts of time to think about it, when they’re really 15.5 weeks and the provider goes to 16, then they don’t have that much time to think about it. Playing around with the date of the pregnancy is common and detrimental either way. Patients need accurate information so they know what their options are and how much time they have to make a decision.

WLP: We read about protester men throwing doll parts at young women seeking medical care. That resonates with me because it’s so emblematic of the objectification of women’s bodies by the anti-abortion movement. They think of us in parts. Did any of the stories you collected stick with you?

Yes, a few. One clinic director that we interviewed told us about really massive protests in front of the clinic. Up to a thousand people would protest, and regularly hundreds, with multiple loudspeakers going at the same time, multiple fake clinic RVs parked outside the clinic, and protesters chasing patients into the parking lot. It just seems so unfathomable that this is something patients can and have to get through, to obtain medical care. It’s so demeaning to them and so intentionally obstructive. This would never be accepted in any other area of medicine.

In the area of practical support, there’s a story that stuck with me of an older volunteer who helped a patient from the South who could not be seen at her local clinic because of medical issues. The volunteer drove this patient hundreds of miles to a Washington DC clinic, but that clinic couldn’t see her, so she then had to drive to New York City, where the patient was finally seen. The volunteer stayed with her and drove her home, a 12-hour car ride in a torrential downpour, to get her home to her kids for Christmas. The dedication of the volunteer and the determination of the patient has stuck with me. They had to endure all of that all because there aren’t enough clinics to do this care anywhere near where this patent lives.

WLP: You note near the beginning of the book that while abortion is usually in the news because of yet another unconstitutional restriction being introduced or passed, some states are taking good, proactive measures to increase abortion access. Can you describe the landscape and political moment as you see it?

Progressive legislators are finally waking up and realizing that they can do good by passing proactive laws rather than just not passing anything bad. We’re seeing that in several states, especially since the 2018 midterms. Some states either getting rid of bad laws from their books or passing laws affirmatively increasing access or adding abortion access to their state constitution as a protected right.

I like to point out Maine as the best example because, in 2019, Maine passed two laws that will greatly expand access. They are now going to include abortion as a covered procedure under their state Medicaid and allow advanced practice clinicians, such as physician assistants, nurses, and certified midwives, to perform certain abortions. The combination of those two measures, and considering Maine is a state in which telemedicine is already allowed, will greatly increase access in such a large rural poor state.

WLP: Surveys show Americans choose abortion most often for economic reasons. Specifically, women report having a baby would interfere with work, education, or caring for children or dependents and simply can’t afford it. So why does the pro-life movement oppose basic support for working parents?

They like to talk about supporting children and babies and moms and caring about pregnancy outcomes, but they only say those things when they’re trying to restrict abortion. Otherwise, there’s no support for families, because ultimately they are not comfortable with women’s place in society. They don’t exactly want women to be barefoot and pregnant, but pretty close.

WLP: Maybe in heels.

Sensible flats maybe.

WLP: You wrote about “the myth of uncertainty.” What do you mean by that?

A lot of people believe that every abortion patient is struggling with this decision and tormented by the choice, whereas when it comes to measuring how certain patients are when they go to a clinic, studies show they are as certain if not more certain than any other comparable procedure. Pregnant patients have a good sense of what they want in life and know what their options are and consult with whoever it is they need to consult with for the decision, and when they show up at the clinic, they know what they want. This country has installed all sorts of restrictions around waiting periods, and counseling requirements and minors having to talk with their parents, and they are all unnecessary restrictions based on the notion that ‘Well you know those women are not so sure what they want so we are going to tell them.”

‘We’ being the state.

WLP: I was enraged to read about a doctor advising a patient that her molar pregnancy would “turn into a baby.” It turned into cancer for my friend who had to undergo chemotherapy shortly after learning she could not have any more children. You wrote, “Almost unbelievably, in the state where Jennifer works, this doctor is free to misdiagnose the patient and sabotage her decision to have an abortion without any legal consequence. This is so because her state is one of the roughly half of states that prohibits ‘wrongful birth’ lawsuits.” Please elaborate.

In some states, you are not allowed to sue because a doctor has withheld information that might have led you to decide to have an abortion. These are explicitly anti-abortion laws that permit doctors to lie to patients about pregnancy conditions so they’ll carry to term, and then there’s no recourse for the patient. These laws allow anti-abortion doctors to lie to patients.

WLP: Thanks so much for your work and your time today.

Is your favorite independent bookstores open for online ordering in Pennsylvania? Please let us know!

You can also order Obstacle Course on Amazon.

March 2020: Our physical offices are closed but we are OPEN and working to serve your needs. Contact us here.

The Women’s Law Project is the only public interest law center in Pennsylvania devoted to advancing the rights of women and girls. Sign up for WLP’s Action Alerts here. Stay up to date on issues and policy by subscribing to our blog, following us on twitter and liking us on Facebook.

We are a non-profit organization. Please consider making a one-time donation or scheduling a monthly contribution.